Most importantly, trees are the outstanding stories of survival

by Pratibha Tuladhar

Kathumandu (Nepali Times) — The sound of the wind rushing through the trees as they brush and slide against the foliage, swooshing like a mountain river gently flowing downstream. Not one of those deep gorges but the shallow kinds, where the water hurries over the rocks, shaping them with millions of years of washing. That’s the white noise I discovered recently on Youtube: The wind in the trees.

Depending on the force of wind, the sound changes, ranging from a gentle stream to that of a fierce river– like nature imitating nature.

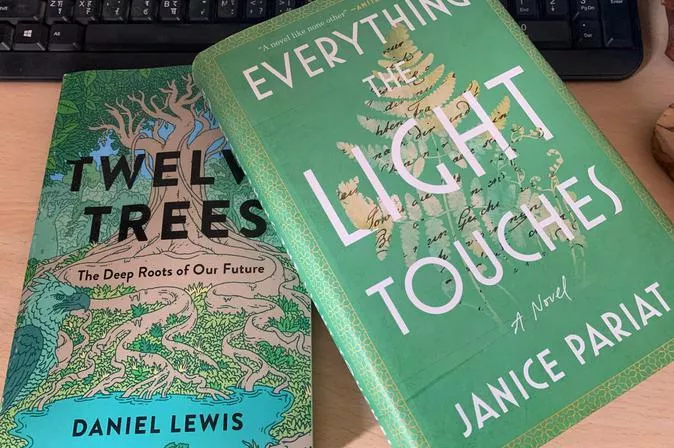

Trees will always mean a million things to me, but recently, they’ve also become synonymous to Janice Pariat. I met Janice through her book: Everything the Light Touches. And I fell in love. The book is the Spring shade of green, letters written on a fern pressed to it. It’s a big, thick book and so makes it a good one to press to your bosom.

I was interviewing Janice for the Nepal Literature Festival in Pokhara in February and so I read the book diligently, the way one does for duty and not for pleasure. I took two days off work to finish reading it, pinned to the nervousness of being singularly engaged in something nice. The book took me on a long journey though Northeastern India and Europe, as I joined each of Janice’s characters’ pursuits.

The novel is a palindrome– it progresses from the story of Shai and crescendos to that of Carl Linneaus’, where it becomes a book of poems. And then it traces each character back again, just as it had started out bringing one home to Shai’s story. And by the time we arrive at the last chapter, we’ve read four novels inside one.

Each chapter has a different voice, making it an entirely different novel in itself, as the characters embark on journeys of self-discovery, in the guise of the pursuit of nature. Each of Janice’s characters is an outlier and each, in search of something. But they all converge in nature in their respective ways.

The novel weaves itself around some really important and relevant topics: of colonialism, post-colonialism, indigeneity, identity, returning to one’s roots, taking only what one needs, and giving back to nature, all of them making us think about the causes of climate change and greed and also goodness.

When I met Janice, one of the things I asked her was how she had written the book. And she did say that it felt sometimes like the book had written itself, even though it had taken her a decade to finish it.

During the festival, when Janice read the prologue, which I like to call the invocation to storytelling, the audience watched enthralled. They leaned their hearts in to listen. she read it like a song. She speaks in singing, almost representative of the book– tender and firm, supple like the leaves when sprouting, sturdy like the trunks that hold the promise of years.

I offered Janice a book review, but how does one review a book one likes, except hold it and read it again? And like a sign, another green book found me: Twelve Trees by Daniel Lewis, steeped in dendrology, but also packed with anecdotes on anthropology and taxonomy, supported by illustrations.

The book is a revelation: trees converse with other trees, have best friends, nurture one another, are the reason butterflies sometimes get caught in amber. Most importantly, trees are the outstanding stories of survival: “Survival takes many shapes. Occasionally, it involves standing your ground. Sometimes it means returning home. At other times, it requires leaving altogether”.

Trees carry memory, even after they have been felled, and their rings bear history. Stories of survival are holding up each tree we see around us– how they navigated the wrath of nature and the stupidity of human kind.

Lewis says, scientists are driven not only by intellectual pursuits but also by astonishment… and that line came back to me last month when I stood under a tree in the heart of Ranibari and stared at an ancient tree, perhaps as Janice’s Goethe might have done at some point?

My friend Nir, a dendrophile himself, watched me marvel at the tree– it stands taller than any tree I’ve met in Kathmandu yet. And it stands there silently, nestling secrets for years, home to many “ghosts residents”, who burrow holes into its trunks and hide between the branches and leaves.

“Go offer water to the Peepul tree and sit under its shade every Saturday,” the priest said, singing off a prescription of forest bath, also repeated by doctors and psychiatrists. And so I go. Seeking.

Trees are so much, they’re myths, each drawing stories to itself and sometimes, lending its name to a place, sometimes to persons, sometimes to entire eras. For instance, the old name for the village I live in, is Chapli, a Newa name for an old tree that did not survive human folly.

Now, other trees remain. Two outside my window, go through the cycle of life in their entirety every year. They become scrawny trunks and branches in Winter and come back in full force in Spring. I watch them from my window like my life depends upon them.

Lewis says: Just as humans stretch and wrinkle and sag with age, trees do, too. And so I imagine these trees are my sisters, aging alongside me, their branches like tresses blowing in the wind some days, and sometimes, weather-beaten and cold, their branches weighing down like sagging breasts. But today, they’re lush green, swaying in the breeze and waiting for the rain. For trees carry the memory of rainfall.

INPS Japan/Nepali Times